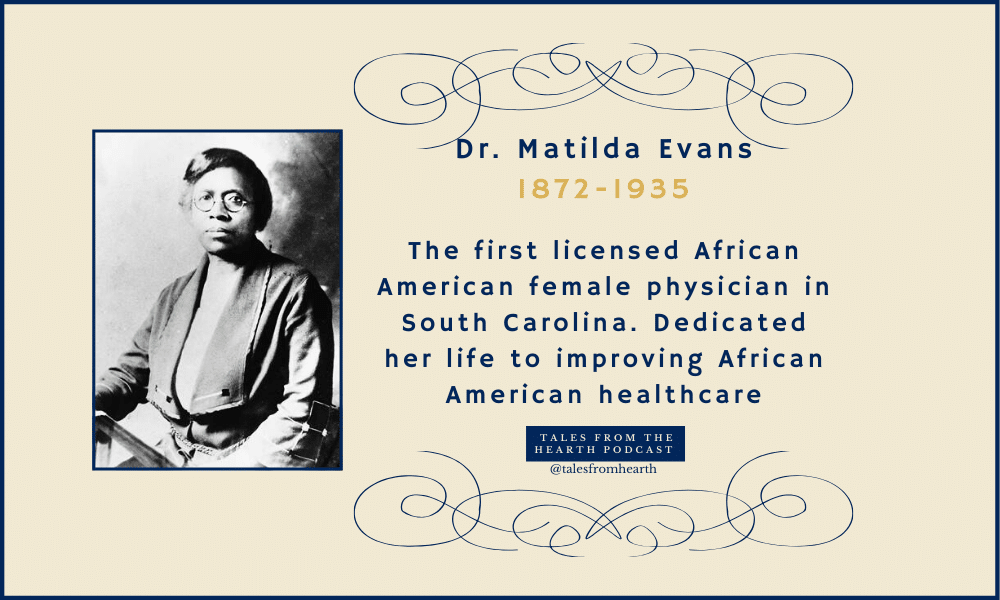

Dr. Matilda Arabella Evans

May 13, 1872 – November 17, 1935

Episode Intro: Did you hear about the first licensed African American female physician in South Carolina? She worked tirelessly to advocate for better health in her home state, changing the lives of thousands—if not millions through her compounding efforts. Join us for today’s episode on the incredible service of physician Dr. Matilda Evans.

Let’s get cracklin’, shall we?

**********

When I read about the incredible life and service that Dr. Matilda Evans provided in her lifetime, I felt that I needed to hustle and work much much harder to keep up with her. I don’t know if Dr. Evans ever slept. She worked tirelessly to provide discounted and free services to the African American community in South Carolina, ministered to clients of all races, vaccinated school children, lobbied for cleaner water and communities, owned her own practice, worked at a local hospital, and did all this while raising eleven children and working on her own farm! Even more incredible, she did this during a time in which she was doubly discriminated against—as a female doctor and as an African American. Wow! I’m so excited to share with you the story about the amazing energy Dr. Matilda Evans brought into the world through her service.

Sources for today’s story are: Many! As always, refer to the episode show notes at www.talesfromthehearth.com that’s www.talesfromthehearth.com. You can find all of the links to the resources for today’s episode on our website.

You can view many photos and links to information about Dr. Matilda Evans on our Pinterest board located at https://www.pinterest.com/TalesfromtheHearth/dr-matilda-evans/.

There’s a great article by Darlene Clark Hine, “The Corporeal and Ocular Veil: Dr. Matilda A. Evans (1872-1935) and the Complexity of Southern History.”

Another helpful resource is a great book about women entitled More than Petticoats: Remarkable South Carolina Women by Lee Davis Perry.

The One Takeaway I hope you get from this story is: You have enough time to accomplish what you prioritize.

Now, I hope you enjoy the story about Dr. Matilda Evans.

**********

Dr. Matilda Evans was born on May 13, 1872, near Aiken, South Carolina, to Harriet Corley and Anderson Evans, former slaves turned sharecroppers. The oldest of three children, she worked endless days picking cotton in the fields alongside her family at a young age, yearning to obtain an education.

Her dreams were realized when she gained admittance to the Schofield Normal and Industrial School located nearby in Aiken, South Carolina. Despite threats of violence, Quaker and native Philadelphian Martha Schofield founded the school in 1868—one of the first high schools in the nation to educate African Americans.

Martha Schofield noticed Matilda’s hard work, wit and potential, and invested extra time and effort into the budding student. Likewise, Matilda idolized the brave Martha Schofield, eventually writing a biography about her in 1916 entitled, Martha Schofield, Pioneer Negro Educator.

Martha Schofield encouraged Matilda’s study beyond the Schofield School, and worked to obtain funds for her to attend Ohio’s Oberlin College. In 1892 Matilda left college before graduation and served as a teacher at the Haines Institute in Augusta, Georgia. Just one year later, she returned to teach at the Schofield School to save up for medical school.

Martha Schofield continued to help Matilda, assisting her in making connections that would help finance her medical education. She was finally able to attend The Woman’s Medical College in Philadelphia in 1893. Even though it could not have been easy being the only African American in her classes, Matilda worked very hard and obtained her medical degree in 1897.

Shortly thereafter, Dr. Matilda Evans returned to Columbia, South Carolina, to start her practice, originally focusing on health care for African Americans. She was the first NATIVE female African American physician in the state (only a few months later than and second to a female doctor who had relocated from in North to South Carolina). Nevertheless, she was the first to be licensed.

Her private practice was incredibly successful. She served as a surgeon, obstetrician, gynecologist, and pediatrician. She treated both whites and African Americans, and was sought after from neighboring states for her care, especially within the fields of gynecology and obstetrics. Notably, she treated white women who preferred a female doctor and one who valued patient privacy. Fees from her wealthier patients subsidized much of the care she provided to the poor.

Matilda felt a calling to do more for the African American community, which made up 40% of the population but had zero access to a hospital. Because it was also difficult for African Americans of this time period to see a qualified physician, they suffered greatly from tuberculosis and a high rate of infant mortality. Dr. Evans treated people in her home until she established the first hospital for African Americans in Columbia, South Carolina. In 1901 the Taylor Lane Hospital and School for Nurses for African Americans was established. The hospital also included a dentist—something previously unheard of for African American care. The space accommodated only 30 patients at first, but expanded and always focused on providing free health care and education.

Dr. Matilda Evans was known for her ability to persuade and motivate people of all races. She communicated regularly with leaders in both white and black communities to achieve common goals. The hospital relied heavily upon volunteer care to provide services, a large portion of whom were white males looking to gain medical experience. She also sold hospital services in addition to her own, setting up paying contracts with major corporations to provide employee health care. She was a great saleswoman!

She continued to reach out to benefactors on behalf of the hospital and other aspiring students in the African American community. Dr. Evans wrote about an aspiring physician in 1907, saying, “I need her…the poor people of her race need her.” Dr. Evans wrote confidently about herself in the same letter, noting, “You may remember me as being the colored student to whom you gave a scholarship in 1893 to The Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania. I graduated in the class of 1897 and came South and have built up, as I must tell you, a most enviable reputation. I have done well and have a very large practice among all classes of people. I have not lost one day since I left College.”

Wow! The statement, “I have not lost one day since I left College” struck a chord with me as an ideal that we should all live our lives by. Can you imagine what we would accomplish if our goal was not ever losing one day? Dr. Matilda Evans was constantly working, writing, and serving others. It seems to mean a lot more today, since we’re able to binge television shows and spend so much time on social media. I don’t see Dr. Matilda Evans doing any of those things if she were still alive today!

Dr. Matilda Evans’ service and character was recognized far and wide, well beyond just her own race. The nurses she helped train were highly sought after by blacks and whites. White attorney John T. Duncan advocated for funding of the Taylor Lane Hospital, stating, “(Evans) the best educated and most intelligent member of her race I have ever known. (She has) the confidences (sic) of the community and the best wishes of the white people.”

Dr. Evans was quite industrious, and filled in gaps where she saw them. In 1916 Dr. Evans started The Negro Health Association of South Carolina. This entity focused on a weekly newspaper, The Negro Health Journal, that provided much needed preventative health education. When her beloved Taylor Lane Hospital succumbed to a fire, she was able to move operations into the much larger St. Luke’s Hospital and Training School for Nurses. She operated the second facility until the United States’ entry into World War I in 1918, when Dr. Evans served in the Medical Service Corps.

Dr. Evans was the only black female physician to serve as president of a state medical association, the Palmetto Medical Association, in 1922. She also served as president of the Colored Congaree Medical Society, regional vice president of the National Medical Association, and as a trustee of Haines College in Augusta, Georgia (where she once worked as a teacher).

Even through the Great Depression, Dr. Evans continued to provide free and discounted care. She greatly concerned herself with the welfare of African American children—who often went without immunizations or regular medical exams. She provided care in nearby schools, funding exams, tests, and much-needed vaccinations. Her observations and data regarding pediatric illnesses moved the school system to add physical exams to its standard requirements for students of all races.

Dr. Evans was very persuasive and used teamwork, data, and the media to obtain better solutions for African Americans. “I am determined—I have sworn it—that…our children shall not be deprived of the advantages which a first class, most modern clinic can give.” Through her leadership, funding for the Columbia Clinic Association was successfully obtained. Starting in 1930, it provided free care for African American pregnant mothers and children.

Did I mention that during this time, Dr. Evans raised eleven children? Eleven. She never married or had her own children, but raised five of her nieces and nephews in addition to six others without homes. She was an adoptive and foster parent for more than two dozen children, and she and her family lived on a twenty-two acre farm with animals, fruits and vegetables that needed continuous attention as well.

Her hobbies included knitting, dancing, and playing the piano. She rarely missed services at St. Luke’s Episcopal Church, and served as an officer in the Upper Diocese of South Carolina.

Dr. Evans also taught herself how to swim. She also founded a recreational program for boys, opening a pool for them, while at the same time providing a place where African Americans could learn how to swim.

I don’t know if she ever slept!

Dr. Evans did not escape criticism, however. Many thought that she should advocate for desegregated facilities instead of just obtaining funding for segregated facilities. She was also accused of working too much with those in the white community, especially when she allowed white male doctors to provide much of the medical care in exchange for the opportunity to gain experience.

Dr. Matilda Evans continued to advocate for better African American health care, education, and funding throughout the Great Depression. She passed away suddenly from a cerebral hemorrhage and kidney inflammation on November 17, 1935. Her initiatives continued despite her death, carried on by the actions she took to unite the community.

Her advocacy saved the lives of thousands, if not millions, through the compounded effects of instituting health care and exams in schools.

Her home on 2027 Taylor Street in Columbia, South Carolina, bears a historical marker with her legacy of service.

That’s it for today! I hope you enjoyed today’s story about the remarkable feats of service that Dr. Matilda Evans accomplished. Her legacy lives on in the many descendants of the thousands of people she helped.